Anchoring the Arctic

Economic Statecraft for the Northwest Passage

Ben Kallas

Executive Summary

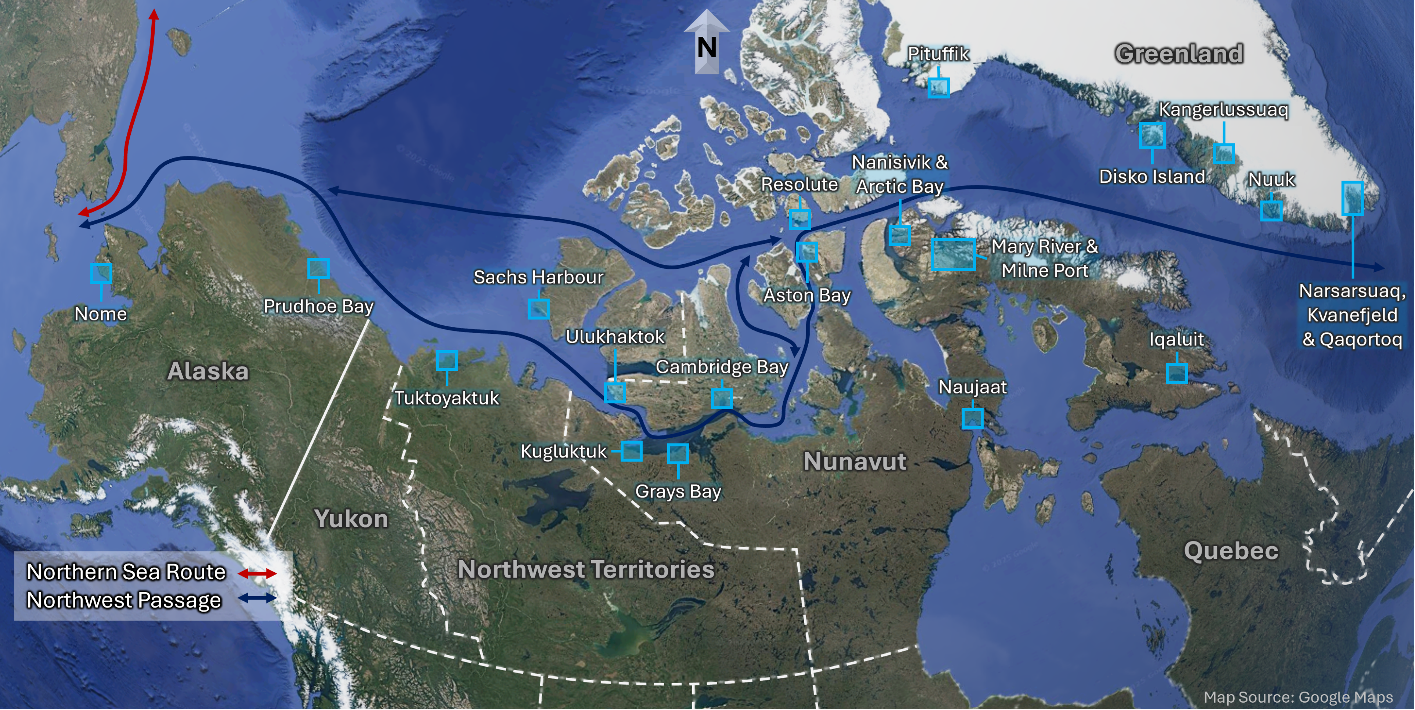

The Arctic is rapidly emerging as the world’s next strategic frontier. Receding sea ice will likely enable commercial ships to transit polar shipping routes, including the Northwest Passage, as soon as the late 2030s. Container ships can already transit the Northern Sea Route, which passes over Russia. Both routes are considerably shorter than existing maritime options. Vast reserves of critical minerals and natural gas will also become accessible across the Canadian Arctic and Greenland. The countries that develop the physical infrastructure, commercial activity, and maritime logistics to maintain presence and project force throughout this vast new frontier will reap geopolitical dividends throughout the 21st century. The United States and Canada are off to an uninspiring start.

Today, the Western Arctic, which stretches from northern Alaska through the Northwest Passage to Greenland, remains largely undeveloped. The United States and Canada face a familiar dilemma: infrastructure projects cannot attract capital without commercial activity to generate cash flows, but commerce requires a minimum level of infrastructure. This paralysis leaves a vacuum – one that strategic competitors are positioning themselves to exploit.

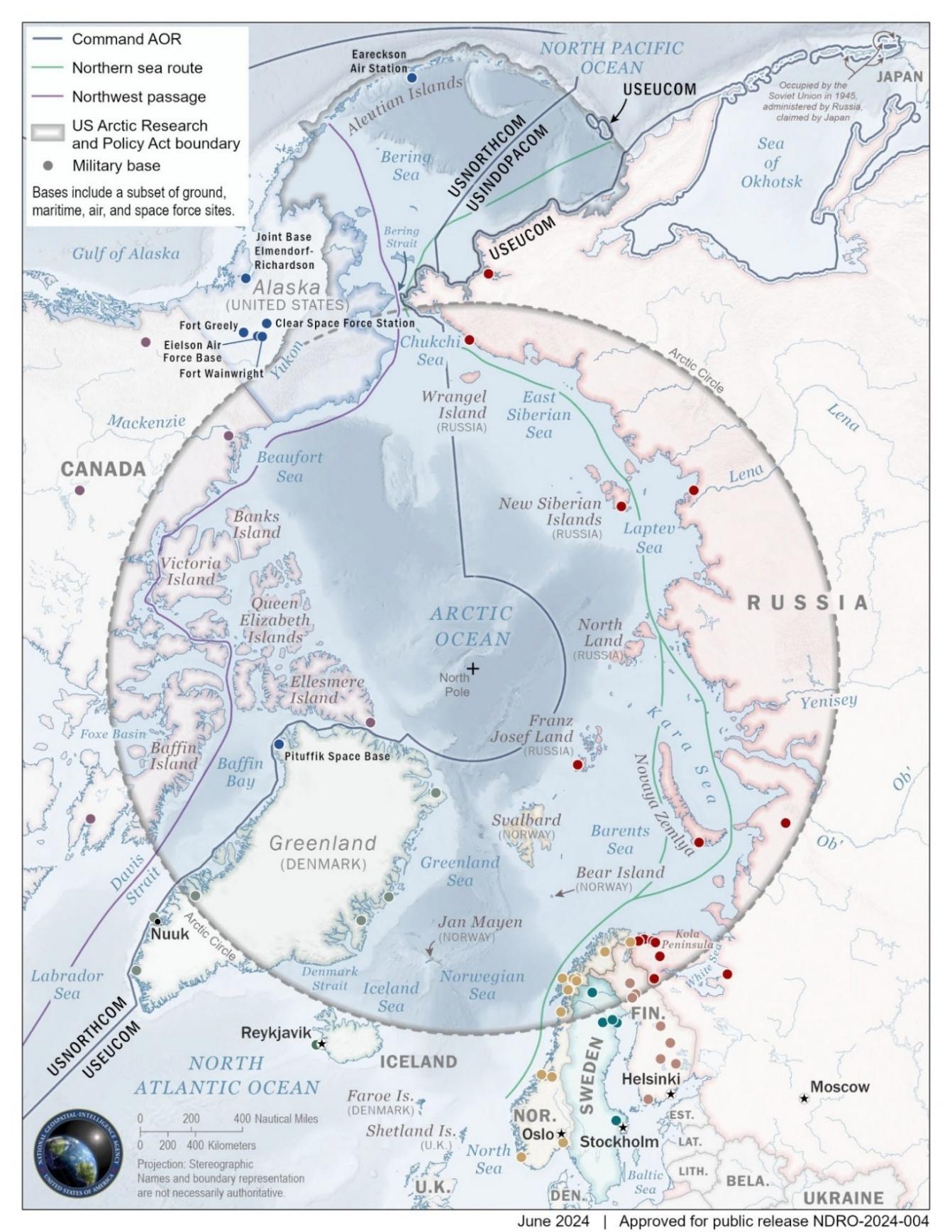

Russia has spent the past two decades revitalizing and expanding upon Soviet-era Arctic infrastructure to enable a persistent and increasingly economically sustainable presence along its northern seaboard. It maintains roughly 10 times more heavy icebreakers than do the United States and Canada combined, which facilitates commercial and military access to its Arctic ports, even in winter. Its Arctic Command overseas the powerful Northern Fleet and well-equipped land forces. China, through its “Polar Silk Road” and state-backed investments, is leveraging dual-use science and commerce to secure regional access and influence.

The timeline for strategic infrastructure development along the Northwest Passage is starting to compress. If climate forecasts are even remotely correct, the region will become accessible in the summertime – and thus open to geopolitical competition – within roughly 15 years. It will take at least that long to site, permit, and build the ports, airfields, energy infrastructure, and roads that enable large-scale commercial activity and thereby generate a sustainable regional presence.

This proposal outlines a strategy of economic statecraft to break the development deadlock in the Western Arctic before adversaries shape its future. It argues for an international initiative, led by the United States and Canada but closely coordinated with Denmark and Greenland, built on four interlocking pillars:

The United States and Canada should co-invest in dual-use Arctic infrastructure – deep-water ports, modern airfields, energy, and logistical hubs – that enable defense operations and lay the foundation for future commercial activities. With those prerequisites in place, public funding and offtake agreements can crowd in private investment and foster commerce throughout the region.

The United States should resolve a crucial point of tension with Canada by offering conditional recognition of Canadian sovereignty over the Northwest Passage in exchange for guaranteed transit rights, permanent port access, pre-agreed levels of infrastructure and maritime enforcement capabilities.

The United States should invest in Greenland’s infrastructure and mining sector to establish critical minerals access and force projection capabilities that complement Canadian installations. Such infrastructure will create an eastern anchor to the Northwest Passage.

Development should proceed through genuine cooperation with Indigenous and local communities, both for moral reasons and because those communities can slow or halt Arctic projects that do not serve their interests.

This approach embeds long-term North American control over an emerging global trade and resource extraction corridor. It preempts Russian militarization and Chinese economic encroachment by establishing a resilient, rules-based framework before the region’s geopolitical character hardens. It ties Arctic development to local prosperity, securing political legitimacy and enduring public support. And it reaffirms U.S. leadership – not by reacting to crises, but by shaping conditions in advance.

Problem Statement

The Arctic is warming nearly four times faster than the global average, which will likely usher in a period of transformation that will prove irreversible over the coming decades. Retreating sea ice is redrawing the global map and opening new maritime routes across the top of the world: the Northwest Passage over Canada and the Northern Sea Route over Russia. Both are on track to become shorter, cheaper, and safer shipping routes between Europe and Asia. The Northwest Passage is expected to facilitate summertime commercial shipping as soon as the late 2030s, with the potential for year-round commerce later in the century. Commercial vessels regularly transit the Northern Sea Route already. Chinese container ships did so seven times in 2023, including the NewNew Polar Bear, which dragged its anchor along the seabed for 180km and damaged a Finnish natural gas pipeline.

Receding ice and thawing permafrost will also permit access to vast, untapped reserves of critical minerals, including heavy rare earths, uranium, and nickel. Greenland and northern Canada sit atop some of the world’s most strategically valuable deposits of such minerals, and the emerging shipping lanes offer an opportunity to connect those materials to global markets.

Russia and China – though primarily Russia – have invested far more resources into Arctic operations than have the United States and Canada, as the next section explains in detail. Western adversaries are playing the long game, investing in infrastructure today to entrench their influence in the next major theater.

It does not help that the United States and Canada disagree over the legal status of the Northwest Passage. Canada claims the route as internal waters while the United States treats it as an international strait. This ambiguity causes a political stalemate, precluding a unified North American approach to the region.

The two countries face a narrowing window – roughly 2025 to 2035 – to invest in the assets, access, and alliances required to secure the Northwest Passage and thereby position themselves for the most consequential geopolitical shift of the mid-21st century.

Strategic Context

Vessels transporting goods from Europe to Japan must endure a voyage that involves the Suez Canal, the Bab al-Mandab, the Gulf of Aden, the Strait of Malacca, the South China Sea, and sometimes the Taiwan Strait. The U.S. Navy generally maintains stability throughout the route, though that is increasingly cold comfort for countries like Russia and China. The Northern Sea Route bypasses all these hazards and provides a 40% reduction in shipping distance from Europe to East Asia. The Northwest Passage offers similar distance savings and bypasses the chronically mismanaged, expensive, and U.S.-dominated Panama Canal.

As was noted previously, the Arctic’s long-term economic potential includes considerable natural resource reserves. The region holds as much as 13 percent of the world’s undiscovered oil and 30 percent of its natural gas, along with strategic minerals essential to clean energy, defense manufacturing, and semiconductor production. The new maritime routes offer an opportunity to extract those resources through northern ports, as southward land transportation across thawing permafrost – i.e., endless swampland – is rarely feasible.

The West’s adversaries are moving accordingly. Russia maintains the world’s most powerful icebreaker fleet: 42 total vessels, including eight nuclear icebreakers, one of which is designed to launch cruise missiles. It has also built the land-based capabilities required to sustain commercial and military operations in the region. It is even installing floating and land-based small modular reactors (SMRs) to provide sustainable power to key installations. In short, it can dominate the Northern Sea Route and flank NATO’s northern European perimeter at will. It already cites Article 234 of the Law of the Sea to control its Northern Sea Route, requiring foreign vessels to request permission and pay Russian escort fees.

China, meanwhile, has positioned itself as a “near-Arctic state.” Through its Polar Silk Road initiative, it has invested billions of dollars in infrastructure and mining projects in the Russian and Nordic Arctic, though Canada and Greenland have turned down most Chinese investment overtures. Beijing has also deployed icebreakers and ice-capable research vessels, which are required by Chinese law to share data with the military, has participated in joint patrols with Russian naval vessels near Alaska, and signed a maritime law enforcement agreement with Russian counterparts during a meeting within the Arctic Circle. While China’s Arctic presence is far less robust than Russia’s, such activities suggest a future in which those countries may cooperate to shape northern rules, access, and transit flows in the region.

By contrast, the Arctic remains a strategic blind spot for the West. Between Alaska and Greenland lies a vast, underdeveloped expanse of sea and land, scattered with aging airstrips and tiny, isolated communities powered by diesel flown in at extraordinary cost. There is no deepwater port along the Canadian segment of the Northwest Passage. The United States operates just one medium and one heavy icebreaker while Canada maintains two heavies and seven mediums. Intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) coverage is fragmented, and neither the United States nor Canada maintains persistent naval or air presence across most of the corridor. While North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) modernization has begun – most visibly through over-the-horizon radar upgrades – it remains a defensive posture, not a projection of presence.

The West’s vast resources remain largely untapped, as most sites lack the logistical and energy infrastructure needed to support commercial extraction. No single project – or even any group of projects – can operate in such a remote region while offering attractive financial returns to investors. This situation presents a classic chicken-and-egg dilemma: commerce is impossible without infrastructure, but there is no economic case to build large-scale infrastructure in a remote region with highly uncertain cash flows.

Compounding this is a long-standing legal disagreement between the United States and Canada that hinders cooperation. Canada claims the Northwest Passage as internal waters, giving it the right to regulate transit, enforce environmental standards, and deny foreign military access. The United States, citing customary international law and its global commitment to freedom of navigation, considers the passage an international strait. Canada is reluctant to invest heavily in enforcement or infrastructure without assurance of U.S. backing. Washington, in turn, fears that recognizing Canadian sovereignty might undermine broader global norms around freedom of navigation and trigger immediate challenges by Russia and China.

While the two sides have operated under a practical understanding since the 1988 Arctic Cooperation Agreement, the inconsistency of their underlying positions is unsustainable. It weakens Canada’s ability to assert control and deters the U.S. from fully investing in infrastructure or security protocols that might imply legal recognition. More importantly, it allows adversaries to challenge both states’ credibility. Until the United States and Canada speak with one voice on the status and governance of the Northwest Passage, they will be strategically outmaneuvered by powers that are less constrained by legal caution and more willing to establish facts on the ground.

Russia’s Arctic superiority is hardly confined to the eastern hemisphere, as the Northwest Passage shares a common terminus in the Bering Strait and ice-capable vessels can readily access either route. Neither Russia nor China currently has strong incentives to attempt to enforce their will on the North American side – for now. But it looks increasingly probable that those countries will have the icebreakers, warships, physical infrastructure, and commercial presence to control Arctic shipping lanes and interfere with Western commercial activities by the time the region becomes truly strategically significant. Given the timelines involved in infrastructure construction, the United States and Canada are running out of time to prepare for the foreseeable challenges of the 2030s and 2040s.

Policy Proposals: Four Pillars of Arctic Economic Statecraft

Infrastructure as Statecraft

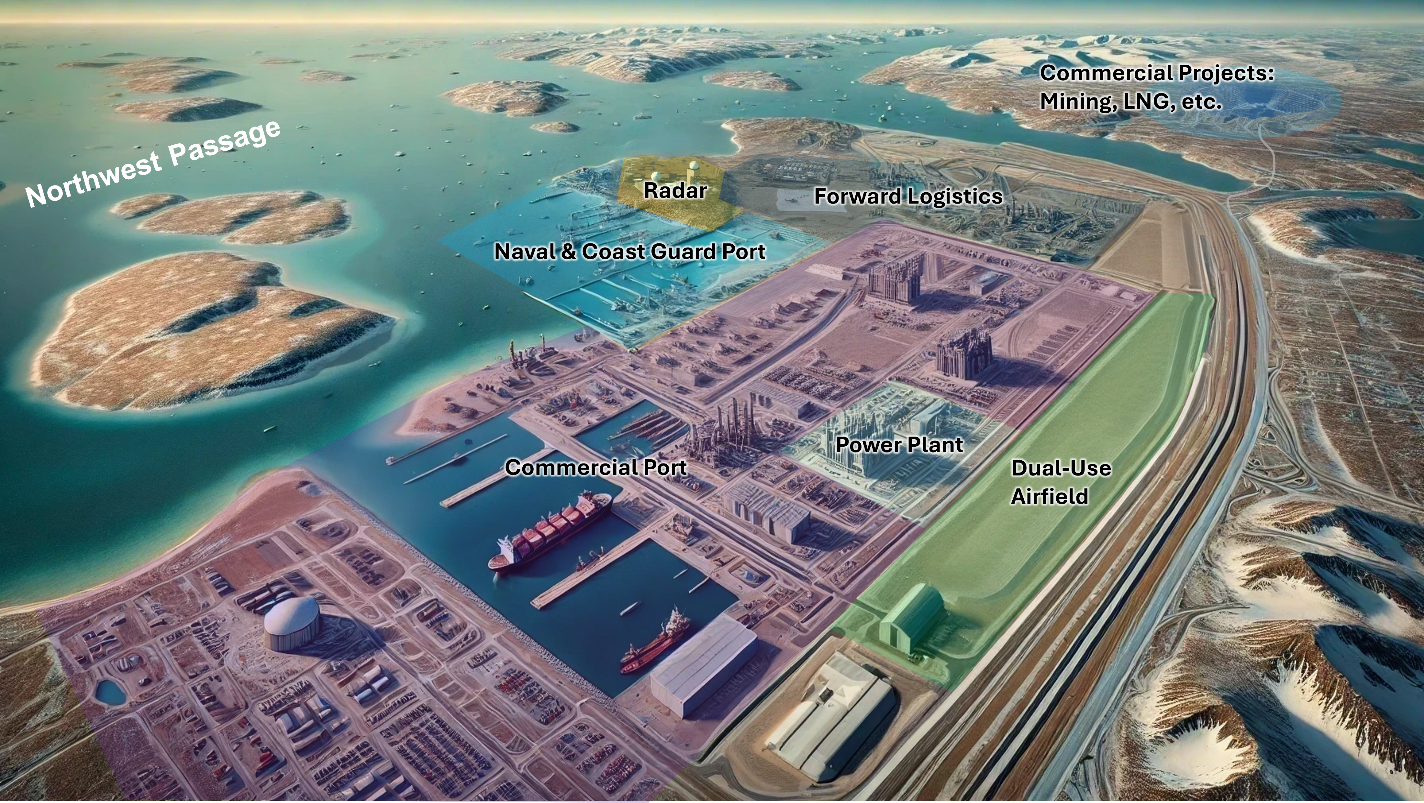

In a region where terrain, distance, and weather dictate what is possible, infrastructure and logistics determine outcomes. Ports, airfields, icebreakers, energy systems, and ISR nodes are not merely logistical assets; they are instruments of statecraft. They determine who can move, who can extract, and who can project force. The U.S. government clearly recognizes this, as President Trump announced in late June 2025 that his administration is negotiating to purchase as many as 15 Finnish icebreakers.

To succeed, we will need deliberate sequencing. Arctic infrastructure cannot be built all at once, and it cannot be driven solely by commercial logic. Governments must lead by building assets that make military presence sustainable and economic activity viable. This begins with strategic siting studies that identify locations near mineral basins and natural harbors capable of supporting both extraction and resupply. Expeditionary airfields and wharves will provide initial lifelines for personnel and material. From there, deep-water ports can facilitate year-round logistics at reasonable cost, followed by scalable power generation. Roads and power transmission lines come last and may be funded by commercial mining and natural gas projects.

Throughout this process, design must prioritize dual-use functionality which serves civilian and military objectives with the same infrastructure. Ports should support mineral exports and food imports, as well as naval repair and oil spill response capabilities. Similarly, runways should support passenger aircraft, C-17s, and Group 5 unmanned aerial systems. Every dollar spent can advance multiple objectives.

Canada and the United States have the institutional tools to finance this effort; however, coordination and clear roles are essential. In Canada, the Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB) is best suited to fund revenue-generating projects: ports, airfields, SMRs, and logistics hubs. Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada (HICC) can support smaller-scale community assets such as roads and airstrips, especially through its rural and northern infrastructure programs. Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) brings critical minerals expertise, energy financing tools, and pre-development funding for enabling infrastructure.

In the United States, a reauthorized and newly empowered Development Finance Corporation (DFC) could invest in Canada and Greenland, provided it is granted a waiver to do so. It is well-positioned to support privately sponsored ports, energy projects, and mineral supply chains. The Department of Defense (DoD), through Title III of the Defense Production Act and the Office of Strategic Capital (OSC), offers the most flexible and unconstrained public capital, particularly for dual-use or minerals-related infrastructure. The Export-Import Bank (EXIM) has more limited utility but can support projects with substantial U.S. content, such as SMRs or logistics equipment.

These funding sources are mutually reinforcing. A forward logistics hub in Greenland could be co-financed by DFC and CIB. An SMR deployed in Alaska might draw from DOE, OSC, and EXIM. NRCan could fund access roads to a mine whose port is financed by DFC and operated under the Canadian flag. Such partnerships are perfectly feasible with appropriate coordination, though private investors will still wonder whether public capital commitments can survive multiple political administrations’ shifting priorities. Any public capital commitments or offtake agreements should include terms that dissuade future politicians from attempting to walk them back.

Several anchor projects illustrate how this can work in practice. In Nunavut, the Grays Bay Port and Road project can unlock numerous mining concessions and establish a logistical and disaster response hub along the central Northwest Passage. Nanisivik – Canada’s long-delayed Arctic naval facility – can finally serve as a year-round staging point and monitoring site along the eastern end of the Passage. In western Greenland, a deep-water port near Nuuk or Maniitsoq can serve both commercial and strategic needs by anchoring U.S. and Greenlandic logistics. In Alaska, the expansion of Nome and Prudhoe Bay, combined with the deployment of SMRs, would establish a true western terminus for the Northwest Passage.

These investments will also help Canada meet its NATO obligations, as it recently committed to spending 5% of its GDP on defense and defense-related initiatives. Under the 2025 Hague Summit Declaration, members will spend up to 1.5 percent of GDP “to protect our critical infrastructure, defend our networks, ensure our civil preparedness and resilience, unleash innovation, and strengthen our defence industrial base.” Most Arctic infrastructure projects will meet those criteria. Canada’s 2024 GDP was USD 2.2 trillion, which would unlock up to USD 33 billion in annual infrastructure-related investments.

Conditional Recognition of Canadian Sovereignty over the Northwest Passage

To facilitate a unified North American approach to the Arctic, the United States should offer conditional recognition of Canada’s claim that the Northwest Passage constitutes internal waters, in exchange for specific, enforceable guarantees. These conditions would include unrestricted U.S. access for both civilian and naval vessels, long-term port and basing rights at key Arctic locations, and a Canadian commitment to invest in credible monitoring and enforcement across the passage. Framed as a bilateral security arrangement rather than a public legal precedent, this approach would resolve a long-standing disagreement while strengthening North American control of the Arctic.

The United States’ current position on the Northwest Passage prioritizes global freedom of navigation over formal recognition of Canadian sovereignty. But this neither compels Canadian enforcement nor prevents adversaries from exploiting the region’s legal ambiguity. Meanwhile, the risk of China or Russia using this divergence to undermine allied claims elsewhere – particularly in the South China Sea – has become more acute. By reframing the issue as one of operational control and burden-sharing rather than legal doctrine, Washington can secure its core interests without undermining its global maritime position.

Conditional recognition offers a path forward. In exchange for diplomatic acknowledgment, Canada would guarantee transit rights for U.S. vessels and commit to sustained investment in Arctic enforcement infrastructure. The latter would include deploying air and maritime domain awareness systems, building Arctic airfields and naval facilities, and making ports like Nanisivik and Iqaluit available for long-term U.S. access. Washington can reduce the risk of immediate sovereignty challenges by delaying recognition until the region attains pre-agreed levels of infrastructure and enforcement capabilities.

The strategic payoff is twofold. First, it creates strong incentives for Ottawa to treat Arctic sovereignty as a function of presence, not posture – triggering investments that would otherwise languish amid political inertia. Second, it embeds the United States in the Northwest Passage’s enforcement architecture, ensuring the region is governed by allies rather than contested by rivals. Crucially, the deal would formalize a joint-control framework that binds U.S. and Canadian interests without prematurely exposing Canada to legal challenges from third parties.

In an era of rising Arctic competition, ambiguity is no longer a viable policy. Conditional recognition offers an opportunity to turn a diplomatic impasse into a strategic advantage by reinforcing Canadian sovereignty, safeguarding American access, and consolidating binational control over one of the world’s most consequential emerging waterways.

Greenland as a Strategic Anchor

If Alaska anchors the western gateway of the Northwest Passage, then Greenland is its essential eastern counterpart. Its location at the confluence of the North Atlantic and Arctic Ocean makes it uniquely suited to host forward basing, early warning systems, and dual-use infrastructure that can support both force projection and economic development. As the Arctic becomes a viable transit corridor and a contested security space, Greenland presents an opportunity for the United States to build enduring geopolitical leverage on a foundation of physical presence, economic inducement, and allied cooperation.

Greenland sits astride one of the most consequential chokepoints of the 21st century, for it also overlooks the “GIUK” Gap between Greenland, Iceland, and the UK – a vital naval gateway for Russian submarines and a key surveillance node for monitoring North Atlantic maritime traffic. The northern installation at Pituffik Space Base (formerly Thule Air Base) already provides missile warning and space domain awareness as part of the U.S. contribution to NORAD. Yet the island’s potential extends well beyond that base.

Upgrades to airports at Kangerlussuaq, Narsarsuaq, and Qaqortoq would enable regular C-17, ISR aircraft, and rotational fighter unit deployments. Ports at Nuuk, Qaqortoq, and possibly Ilulissat could accommodate U.S. Coast Guard cutters and resupply vessels during the ice-free season. With targeted investment, Greenland could anchor a persistent, multi-domain U.S. presence across the eastern Arctic.

That presence should not be exclusively military, as dual-use investments will yield immediate returns for Greenlanders while supporting American objectives. Reinforcing airfields and ports expands logistical reach not only for defense operations but for search and rescue, disaster response, mineral exports, and general commerce. The same infrastructure that enables U.S. basing could also unlock stranded resource projects across southern and western Greenland, including critical minerals like heavy rare earths, uranium, and nickel.

This approach will require deft coordination with both Denmark and Greenland. The U.S. already operates in Greenland under long-standing defense agreements with Copenhagen, and Denmark’s recent Arctic defense agreement allocates USD 2 billion toward naval vessels, ISR capabilities, and training over the next decade – an inadequate sum, but better than nothing. However, while Denmark retains formal sovereignty over Greenland, the latter’s elected leaders are increasingly assertive and open to direct economic engagement. Greenland may pursue independence within a few years, and neither Danish nor Greenlandic leaders appear interested in turning Greenland into an American state or territory. For now, Washington’s safest route is probably to coordinate regional defense initiatives with Denmark – with Greenlandic input – while working directly with Greenlanders on commercial deals.

Just as important, Greenland offers insurance. While Canada has pledged significant Arctic defense and infrastructure modernization for years, it has yet to follow through on its words with action. Greenland allows the United States to secure the eastern end of the Northwest Passage even if Ottawa continues to delay. It also provides staging and redundancy for joint operations spanning Greenland, Iqaluit, Nanisivik, and Alaska. Integrated properly, these hubs form comprehensive logistics and surveillance architecture across the entire corridor.

Indigenous and Local Co-Development

Under current policies, Arctic infrastructure strategy cannot succeed without the support, participation, and shared benefit of northern communities and territorial governments. For instance, in Canada, territorial and Indigenous actors control not only access to land and labor but also the legitimacy and operational continuity of any project. The phrase “Nothing about us without us” is a fundamental principal. This paper assumes that Canada and Greenland will not fundamentally overhaul longstanding Indigenous rights policies and entrenched legal frameworks in the near term, even if they are increasingly at odds with those countries’ long-term geopolitical interests.

Most cultures in the Western Arctic traditionally view land and natural resources as communal property. Private ownership and resource extraction for profit are, for the most part, foreign concepts which are only grudgingly accepted. At a minimum, communities expect that new infrastructure will serve them, not just external actors. Projects that merely facilitate mineral exports or military logistics tend to encounter effective resistance, whether through regulatory hurdles, political backlash, or informal obstruction.

That said, it will not be difficult to benefit local communities. The Canadian territories’ and Greenland’s combined population is only about 185,000 people, most of whom live in spartan conditions. If a multi-billion-dollar project allocates even 1% of its total expenditures to local community initiatives, the nearby towns will benefit tremendously. The key is to understand each community’s unique requirements and allocate capital accordingly; this already standard practice among Western natural resource and infrastructure development companies.

More than infrastructure, communities expect a degree of ownership and participation, including local hiring guarantees, job training, procurement preferences for Indigenous- or community-owned firms, and, increasingly, revenue-sharing mechanisms. Canada formalizes expectations through legally binding Impact and Benefit Agreements (IBAs), which include profit-sharing, labor quotas, and environmental co-management. Alaska Native regional corporations utilize their landholdings to structure joint ventures and lease agreements that return royalties directly to shareholders. Greenlandic lands are publicly owned, but municipal governments and public consultations factor heavily into project approvals. Across these contexts, the most successful projects are those that embed economic, social, and political benefits into the structure of the deal itself.

Governance is equally important. Project managers cannot consult with communities – particularly Indigenous governments – after decisions have been made. Governance participation may include formal roles in oversight boards, hiring panels, and environmental review processes. Projects that bypass this reality, or treat consultation as a procedural box-check, tend to fail or face sustained opposition.

For the United States, the timeline is unforgiving. Trust-building in the North takes years, and permitting processes in Canada and Greenland could stretch over multiple political cycles. The U.S. government could seek to bypass the practices described above for crucial projects that encounter unreasonable local resistance, but it should only do so as a last resort. Meaningful community engagement ought to form Phase Zero of every Arctic infrastructure project, and those projects should seek to benefit local communities even as they enhance state power.

Implementation Strategy

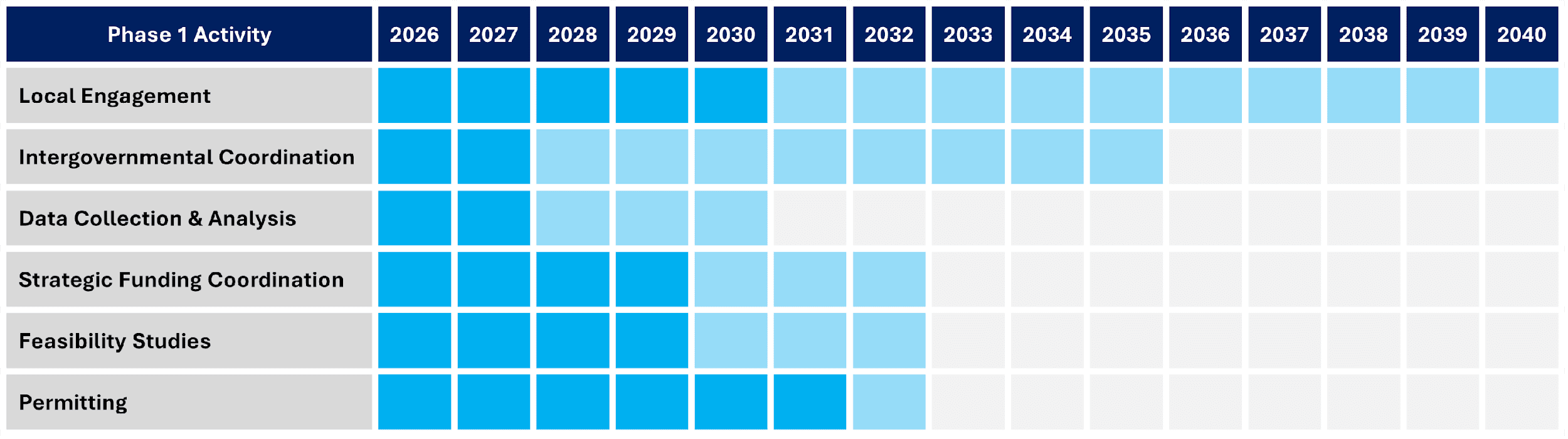

The above policies require a deliberate, time-bound implementation plan. This section proposes a three-phase strategy to break the Arctic's infrastructure deadlock and build toward sustained U.S.-Canadian control of the Northwest Passage. While the full arc spans fifteen years, the first steps should begin immediately.

Phase 1: Foundational Work (2025–2028)

The next three years will determine whether the Arctic becomes a strategic asset or remains a missed opportunity. This phase focuses on laying institutional, political, and logistical foundations for construction and long-term economic development.

Sustained engagement with Indigenous communities in Alaska, Canada, and Greenland will be critical, as they are both politically powerful and generally distrust outsiders after decades of broken promises, paternalistic attitudes, and mistreatment. The engagement teams should include a mix of Indigenous personnel, senior Special Forces veterans with cold-weather training and experience empowering locals in austere environments, and government representatives with the authority to make decisions. Early conversations must not attempt to dictate terms. They need to focus on reestablishing trust, identifying local problems, and finding ways to ensure proposed infrastructure projects address each community’s unique challenges. That process may take years.

In parallel, coordination among the United States, Canada, Denmark, and Greenland must begin as soon as possible. A joint working group should align priorities across infrastructure, basing access, permitting, and logistics. Site selection will require a mix of military and economic considerations. For example, ports must account for bathymetry, seasonal ice conditions, local community approval, and more – yet they should also support inland mining and natural gas fields. Very few locations will meet those criteria.

Feasibility studies and associated assessments will inform permitting pathways, engineering designs, and fundraising. These should begin as soon as project developers receive permits to access potential project areas and begin acquiring data. A coordinated and expedited permitting strategy across jurisdictions will be essential, given the current regulatory terrain in the Arctic.

To manage this complexity, Washington could establish an office with enough authority to synchronize U.S. interagency efforts and coordinate with Canadian, Danish, and Greenlandic counterparts. The DoD's Arctic Strategy and Global Resilience Office could form the nucleus of a far more robust organization that can collate interagency inputs, establish priorities, overcome bureaucratic roadblocks, coordinate funding, engage project managers, and oversee project execution in coordination with Canada and Greenland.

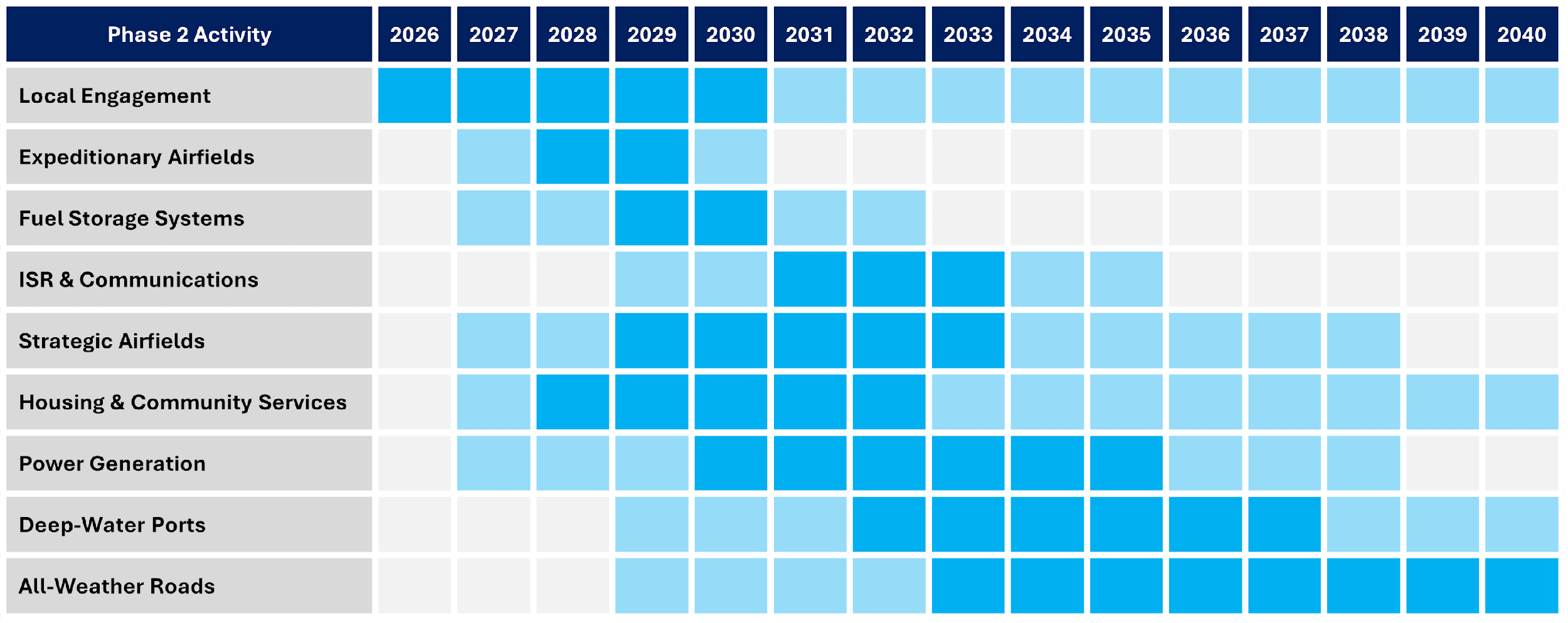

Phase 2: Infrastructure Construction (2028–2033)

Phase 2 focuses on building the enabling architecture for sustained Arctic access. Many potential infrastructure sites – Cambridge Bay and Kugluktuk, for example – have airstrips that will require upgrades to accommodate the influx of aircraft, materials, and personnel to build ports and energy infrastructure. Very remote areas, such as Grays Bay, may require temporary docks or wharves to facilitate the offloading of materials. These steps will create the initial logistical capacity that enables the construction of strategic airfields and deep-water ports.

Energy and mobility come next. Fuel depots and hybrid microgrids – including SMRs in the U.S. context – can power forward operating sites. Transmission lines and seasonal logistics roads should follow, connecting remote communities and mineral prospects to key air and maritime hubs.

Attracting private capital for Arctic infrastructure may initially prove difficult due to long timelines and commercial uncertainty. In the early stages, financing will likely be predominantly public. However, the U.S. DoD and Canadian DND can de-risk investment by acting as anchor tenants, signing long-term leases and power offtake agreements to guarantee revenue streams.

These measures will not guarantee that commercial actors and private capital will flow into the Arctic – but they will set conditions that make commercial activity possible. Investors will still need to consider risks related to future policies, project execution a harsh environment, continued Indigenous support, macroeconomics, future climate trends, actions by geopolitical competitors, and more. This means that most early projects will still require public financial and insurance support to attract private capital at scale.

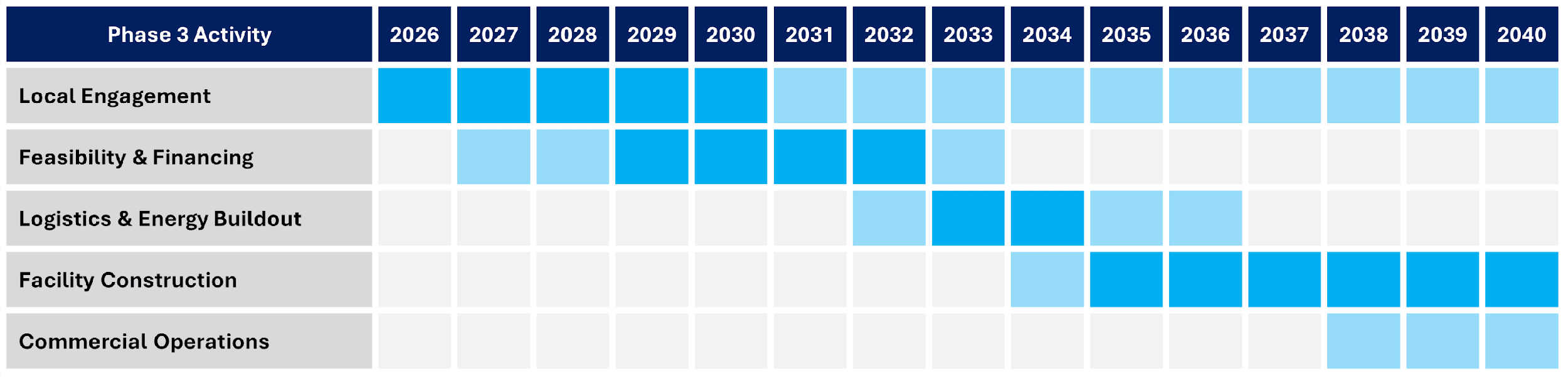

Phase 3: Commercial and Strategic Expansion (2033–2040)

Once the backbone is in place, Arctic development can scale, both economically and strategically. Commercial projects such as rare earth extraction in Greenland, nickel and uranium mining in Canada, and LNG production can begin construction once government-led initiatives yield enough roads, energy systems, and transshipment capabilities.

Military posture will also transition from episodic to enduring. Forward-based ISR assets, upgraded communications, and prepositioned logistics will allow U.S. and Canadian forces to operate with greater persistence and awareness across the region.

Crucially, Indigenous communities should play a key role in driving this development. By this phase, Indigenous corporations and local governments will likely hold operating stakes in logistics firms, service contracts, and even upstream mining ventures. These partnerships will not only reinforce Arctic sovereignty, but also build the local capacity required to manage complex economic ecosystems.

This phased approach – anchored in early engagement, disciplined infrastructure buildout, and shared economic benefit – offers the United States and Canada a narrow but actionable window to assert control over the Northwest Passage.

Strategic Payoffs and Risks

The most immediate payoff is geopolitical. A network of dual-use ports, airfields, and logistics hubs would allow the United States and Canada to control both ends of the Northwest Passage before it becomes a contested global chokepoint. Forward presence in Greenland and Alaska, combined with conditional U.S. recognition of Canada’s claim to the passage as internal waters, would reinforce North American sovereignty while preserving U.S. freedom-of-navigation equities. This cooperative framework would also serve as a counterweight to Russian militarization of the Northern Sea Route and China’s effort to brand itself a “near-Arctic state” through its Polar Silk Road initiative. Upgraded infrastructure would enhance early warning systems, maritime domain awareness, and naval mobility, while securing Greenland as a long-term anchor for Western logistics, diplomacy, and power projection. Perhaps most importantly, it would allow the United States to lead in defining Arctic norms on transit governance, resource extraction, and dual-use development before others do.

Economic statecraft is no less central. The Arctic contains vast deposits of rare earths, uranium, nickel, and other strategic minerals, most of which are currently stranded by cost, logistics, or both. Public infrastructure can break this deadlock by reducing upfront costs and crowding in private capital. It also provides the United States a rare opportunity to embed itself in critical mineral supply chains before China dominates the space. Ports and logistics corridors built for mineral exports will also support commercial shipping and aviation, laying the foundation for a North American Arctic economic corridor. If structured carefully, these projects can deliver tangible benefits to Indigenous and local communities, building the political legitimacy and social trust that adversarial capital often lacks.

Of course, this approach also involves risks. Half-measures or delays could leave the field open for China and Russia, who are already funding Arctic projects across the critical minerals, energy, and telecommunications sectors. A poorly handled recognition of Canadian sovereignty over the Northwest Passage, particularly if viewed as a concession, could establish a problematic legal precedent for other contested waterways. Meanwhile, failure to deliver local benefits or to consult early and often with Indigenous governments could spark backlash that stalls projects. Finally, if Arctic infrastructure is framed too overtly as a containment tool, it could provoke escalation or lead to the very militarization it seeks to prevent. The Arctic’s harsh climate, high costs, and long timelines only compound these challenges.

Conclusion

Great powers shape frontiers by building them. The Arctic is now such a frontier. For centuries, ice has served as a natural barrier to meaningful engagement, but that era is ending. What comes next will be defined by infrastructure, access, and the ability to execute strategies to achieve national objectives. The contours of future competition are already visible: Russia is expanding its military footprint along the Northern Sea Route while China is positioning itself to bypass traditional shipping lanes and access Arctic resources via the “Polar Silk Road.” North America’s current posture – a mix of diplomatic rhetoric, token investments, and strategic ambiguity – will not withstand this pressure.

This proposal offers a framework for action. By investing in dual-use infrastructure, conditionally recognizing Canadian sovereignty over the Northwest Passage, anchoring presence in Greenland and the Canadian Arctic, and partnering with Indigenous communities, Washington and Ottawa can shift the balance decisively.

The cost of inaction is clear. Once rivals entrench themselves, dislodging their influence will be exponentially harder. But if the United States and Canada act now, they can define the rules of Arctic engagement, ensure that mineral wealth flows through trusted supply chains, and secure sovereign control over the future arteries of global trade.

-

Ben Kallas is a former Marine Corps intelligence and reconnaissance officer. He founded Searchlight to help facilitate capital deployment toward strategic overseas projects in 2024 and is now a co-founder of Lorica, a startup building a platform for credentialed labor contracting and compliance to support U.S. reindustrialization.