Abstract: When President Xi Jinping of China launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013 as a part of his great vision for Chinese rejuvenation, institutionalizing and promoting Chinese investments in dozens of countries across the Global South, the United States was ill-prepared to respond. We argue that the United States is still not meeting competitive expectations. This document develops a framework for how the Second Trump Administration can sustain its America First domestic policy objectives while countering the BRI with strong American economic statecraft abroad. Within this framework, we provide (1) a counter-BRI strategy that advises how the administration should prioritize international development investments under America First constraints, (2) suggest two operational theaters for the strategy’s implementation, and (3) offer tactical reforms of U.S. government policy processes related to international development to better fulfill strategic ends.

The Problem Set

In 2013, People’s Republic of China (PRC) President Xi Jinping announced the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to the world as a network of infrastructure, technology, and development projects across greater Asia facilitated by Chinese investment.1 Today, more than 147 countries are either working with the PRC or are interested in getting a BRI investment to stimulate economic growth.2 The scale of the project has been an enormous success for Chinese soft power but worrisome for the American national interests as countries move to align in an increasingly bipolar international order. Former President Biden’s Build Back Better World (B3W) has not proven to be a strong BRI competitor, nor does the United States have a comprehensive and specific counter-BRI strategy to abide by.3 While seemingly incompatible with the Trump Administration’s emphasis on promoting an America First Agenda, it is possible to sustain a domestic policy focus while stepping up to compete with the BRI.

However, before doing so, it must make a critical concession. With an America First agenda in place, the U.S. must accept that China will spend more on foreign investments.4 For one, from the conception of the BRI to 2022, China spent $697 billion on global infrastructure projects compared to the United States’ relatively minuscule $76 billion.5 However, the United States does not need to match China dollar for dollar—it just needs to spend its money more wisely so that its investments generate more positive results than those from China.

Under these assumptions, we present a counter-BRI framework for the Trump Administration that reconciles the simultaneous need for America First and greater American soft power through calculated investment competition with China.

The Alternative Framework

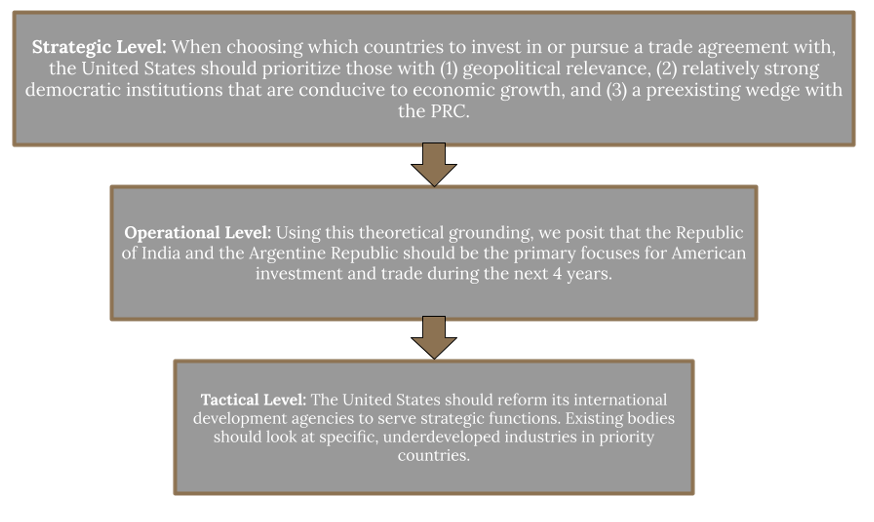

We approach the framework by utilizing U.S. military doctrine for an outline. Thinking about countering the BRI involves three dimensions of thought at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels.6 If the BRI is fundamentally a network of partner nations, countering the BRI will demand a parallel network of American partnerships. However, the assumed concession that the United States must make mean that it cannot have an impact everywhere. Thus, the United States needs an overarching system of prioritization: which countries should receive American dollars first, and which ones can wait? The goal here is to have a repeatable and consistent strategy – backed by logical preconditions – that guides our international development agencies on which projects to streamline. The strategy will output countries that should be primary focuses, which will serve as the operational theatres of this counter-BRI framework.

At this level, this paper will explore the current investment trends in these high-value competition countries and opportunities for greater and optimal American economic involvement. Finally, this framework addresses how the United States should act in these operational theatres. In fiscal year 2024, there were $59 billion of foreign assistance obligations, with nearly $11 billion devoted toward economic development projects—the key assets of American soft power in strategic competition.7 Of this money, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), now folded into the State Department, the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), and the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) are largely responsible for its allocation.8 These agencies must continue to be the vehicles of American development assistance in foreign partners, but should be reformed to better serve strategic functions. We find that individual agency projects are the tactical means of engaging in these operational theatres, and thus, fulfilling the larger strategic ambition of competing with China’s BRI. In the following paper, we will explore the components of this framework and the merits of using it.

The Central Strategy

At the strategic level, three core principles must lie at the heart of an American economic statecraft strategy that seeks to counter the BRI’s intercontinental penetration of potential partners and allies. When choosing which countries to invest in or pursue a trade agreement with, the United States should prioritize those with (1) geopolitical relevance, (2) strong democratic institutions that are conducive to economic growth, and (3) a preexisting wedge with the PRC. A country that meets all these preconditions should be a top priority for the Trump administration to pursue a mutually beneficial economic relationship.

Geopolitical relevance refers to the strategic positioning of a country in the context of the U.S.-China great power competition (GPC).9 It is assessed by examining a country’s proximity to the Indo-Pacific region, its key natural endowments or production capacities that have value to the U.S. and PRC, and its accessibility to global choke points for Chinese trade. The objective is to create meaningful partnerships in the context of GPC, and thus, counter-BRI partners must be geopolitically salient. Furthermore, relatively strong market-governing institutions help ensure robust outcomes from its investment and trade pacts. Democratic institutions are inclusive institutions that create the necessary incentives to encourage citizens to be active stimulants of the economy.10 The United States has an institutional structure that enables Americans to open a business, file a patent, and feel confident that the legal system will protect them from theft or fraud. Instead of coercing countries into democratic alignment, the United States should only engage in countries that have the structural capabilities of being economically productive.11 Countries do not need to be champions of liberal democracy to be viable partners—but they should at least have sufficient democratic qualities so that when the United States invests, it knows its investment will be contractually enforced, protected by IP laws, and eventually completed. Partners that can assure these conditions are high-value investment grounds. Finally, the United States would be wise to look for investment opportunities in places that already have tension with the PRC to split any preconceived wedges further. The United States would save time and money if it did not have to flex its diplomatic muscle to win over already Chinese-leaning states. The United States should exploit any political, economic, or territorial tensions with China by offering a positive, mutually beneficial alternative. The confluence of these three factors creates the Goldilocks conditions for an economic statecraft prioritization system: states that satisfy the criteria are the ideal counter-BRI operational theatres. We present that India and Argentina check all the boxes.

Operational Theatre 1: The Republic of India

Strategic Considerations in India

The first country the Trump administration should court in a counter-BRI economic statecraft strategy is the Republic of India. For one, India’s geopolitical proximity to the PRC makes it a critical opportunity for advancing American economic interests in China’s backyard. India not only shares a northern land border with the PRC, but also has the Strait of Malacca, a critical maritime choke point for the Chinese economy, in its backyard. 60% of China’s trade and 70% of its oil imports pass through the waterway.12

Furthermore, third-party observers, such as Freedom House and Bertelsmann Stiftung, routinely classify India, at a minimum, as a flawed or deficient democracy---recognizing that, despite its imperfections, India still sustains democratic-csque processes and institutions.13 This is a fundamental precondition: the fact that India has elections, an adequate justice system, and prevailing constitutionalism means that the United States can narrow its agenda to economic and geopolitical interests. Freedom House’s “Freedom in the World 2024” report gave India top scores in election freedom and fairness rankings and holds that India’s legal framework “generally supports the right to own property and engage in private business activity.”14 These economic liberties are critical for the sustainable economic growth that investors look for.

As a final baseline, India and China have a history of contentious relations. A core issue is border tensions, as India and China disagree on territorial lines in the northeast part of India and the Kashmir region.15 India has also gravitated toward Western cooperation by recently collaborating with Japan and Australia in maritime security initiatives, creating a wedge in Indian-Chinese relations. Together, these three conditions fulfill the pre-established strategic criteria, and thus, are an invitation to American partnership.

Opportunities in Power Politics

President Trump has emphasized the need to strengthen U.S.-India ties. Modi’s visit with Trump in early February 2025 marked the fourth foreign leader hosted by the White House, notably before any European head of state. By prioritizing India over traditional partners and allies, Trump has signaled an increased focus on developing Indian relations for the future.16 The United States and India have also committed to doubling U.S.-India trade to $500 billion by 2030.17 While not a free trade agreement, this commitment symbolizes an Indo-American realignment that has favorable implications for American economic interests. A joint statement after the meeting reaffirmed India’s “recent moves to lower tariffs on select U.S. products and increase market access to U.S. farm products, while seeking to negotiate the initial segments of a trade deal by Fall 2025.”18 Trump also stated that India may make the US their "number one supplier" of oil and gas in the future, deepening integration.19 In April, the United States doubled its crude oil supply to the subcontinent, “surpassing the UAE to become India’s fourth-largest supplier.”20

Furthermore, the US has gone from a negligible supplier of the Indian armed forces to India’s third-largest arms supplier, with a defense trade nearing $20 billion.21 Due to cost overruns and delays with Russian procurement programs, India seems to be shifting its procurement away from Russian. The United States is a part of a diversification effort that also includes France, Israel, UAE, and South Korea. Meanwhile, while Russia remains India’s top supplier, its share in India’s arms trade has dropped from 62% to 34%.22 Within a strategic context, Trump and Modi further committed to deepening security cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region, an oblique reference to the PRC, as well as to start joint production on technologies like AI.23 After the meeting, Modi reaffirmed that “one thing that I deeply appreciate, and I learn from President Trump, is that he keeps the national interest supreme … like him, I also keep the national interest of India at the top of everything else.”24 Personal politics, strategic alignment, and China as a principal priority are the critical throughlines for the future of American-Indian relations.

Chinese and American Investment Trends in India

Chinese investment in India is salient and responds to ongoing geopolitical trends. Geographic proximity and administrative cooperation have supported a continuing partnership. Data taken from the AEI Global Investment Tracker points to primary Chinese investments being stratified along construction and investment.25 There was a greater prevalence of projects financing energy and industrial investments, such as SEPCOIII in Mumbai, until 2015.26 Following 2015, Chinese flows transitioned to real estate and finance-oriented FDI.27 China’s most recent investment was made by e-sports private conglomerate Tencent in 2022, totaling $160 million.28 China’s most recent construction project was financed by Baowo Steel for 200 million dollars in 2024.29 Since the beginning of China-India diplomatic relations in 1950, total Chinese investment on the subcontinent has amounted to about $16.8 billion.30

Importantly, the investment trends reflect a Sino-Indian partnership outside of the PRC’s Belt and Road Initiative framework. The two countries did have a Bilateral Investment Treaty in place, though they have since broken ties.31 Despite never having formally entered into BRI contracts with India, China has continued to finance development in neighboring states such as Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Afghanistan. Further, India is surrounded by four primary BRI corridors: the BCIM Economic Corridor, the Maritime Silk Road, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, and the Trans-Himalayan Economic Corridor.32 Reports have shown that India’s foreign investment policies have responded to such advances. Though not maintaining the financial breadth of China’s BRI, India has pursued “connection” policies, aiming to establish regional alliances with its partners in response to the perceived security threats resulting from external investment structures.33 China’s hand is deeply involved in the region in BRI. It cares about having South Asia in its orbit of economic influence. Even if Chinese investment in India is dwarfed relative to its neighbors, letting India slip under the strategic radar would be a misstep by the United States and enables future Chinese activity if Chinese-Indian relations improve.

The United States has also built robust investment frameworks with India as the largest contributor to FDI into India in 2024.34 Primarily, finance has oriented itself around infrastructure and development.35 With India’s economic ascendency of growth faster than “any other large nation,” commitment to investment in the United States, and shared concern of Chinese misbehavior, the United States’ engagement in India is favorable.36 The United States has also taken initiatives to diversify supply chain structures by moving elements of production to India, distancing itself from China.37 Reshoring or redistributing essential value chains has continued to insulate U.S. production from Chinese influence and promote cooperation with the Indian subcontinent.

Concerning both American and Chinese investments, the Indian government has maintained a strong domestic outlook on its investment climate. Modi’s government has pushed a “Make in India” policy, bolstering its domestic manufacturing base to alleviate dependency on Chinese imports.38 At the same time, India has loosened restrictions on Indian firms engaging in outward foreign direct investment, enhancing global competitiveness of Indian firms, encouraging economic diversification, and improving India’s soft power.39 Toward China, India has implemented policies to stymie investment relations in recent years. From 2020 to 2022, the Indian government installed new regulations requiring all Indian recipient companies of FDI to seek government approval.40 This has cut into Chinese investment flows. In 2022, only 20% of investment queries were formally approved by India.41 Tensions have been attributed to the 2020 Galwan Valley skirmish between Indian and Chinese troops.42 Following such, investment diversification and a steady distancing from formal partnerships with China have characterized Indian foreign policy. The United States should view this shift in FDI calculus as a favorable opening to facilitate American investment.

Room for American Investment

We find that a critical sector of the Indian economy is its healthcare and pharmaceuticals industry.43 However, India’s energy sector has received the highest number of Chinese investments.44 The United States should use its international development agencies to saturate investments in the former and balance China in the latter.

As the world’s largest producer of vaccines by volume, India supplies nearly 60% of global vaccine demand (primarily through the Serum Institute of India – the largest vaccine manufacturer – and Bharat Biotech).45 The country’s 10,500+ pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities and impressive number of FDA-compliant plants outside of the United States make India an essential component of global pharmaceutical supply chains.46 However, the pandemic exposed bottlenecks in India’s reliance on China for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and key raw materials.47 There is room for the United States to assist in reshoring and near-shoring pharmaceutical production capabilities to trusted partners like India and create R&D ecosystems. The Indian healthcare sector grew 41% between 2022 and 2025, and with the implementation of the National Digital Health Blueprint plan, India aims to “unlock over $200 billion in incremental economic value for the country’s health sector.”48 The massive room for growth makes the Indian health sector a lucrative investment opportunity. India can diversify its supply chain for APIs and raw materials away from China by building domestic upstream capacity, including dedicated API plants and chemical synthesis capabilities, to reduce unit costs. The DFC would be instrumental in this space: loans, equity, and guarantees to Indian API manufacturers or to joint U.S.-India projects can lower financing costs and attract private capital. This would be a win for American companies, the domestic Indian pharma industry, and U.S. competitiveness in light of Chinese API dominance.

On the energy front, India seeks to install 500 gigawatts of non-fossil fuel-based power capacity by 2030, necessitating investment of approximately $30 billion.49 This goal aligns with global climate commitments and India’s energy security objectives. To achieve this, India plans to double its annual renewable capacity additions with a focus on solar and wind energy.50 India relies heavily on Chinese imports of solar cells and solar modules to expand its capacity for solar-powered energy generation, as the domestic supply does not satisfy domestic demand.51 However, the DFC has already participated in equity investments to expand renewable energy generation and storage in India. To build independence from the PRC, the DFC has given a 425 million dollar loan to TP Solar LTD (India’s premier cell and module manufacturing facility) to boost India’s production of solar panels.52 This will simultaneously support approximately 2,300 full-time local jobs.53 This is just a start. In the context of strategic competition, these are win-win investments. The United States shows a commitment to Indian growth while the Indian people reap the benefits of their new energy resources. In high-value competitive operational theaters, international development serves a strategic function that is worth the investment.

Other important industries could benefit from American investment. India’s digital infrastructure is undergoing a rapid expansion. The country’s data center energy demand is expected to increase from 0.9 Gigawatts (GW) in 2023 to 2 GW by 2026, supporting India’s growing digital economy in E-commerce, fintech, cloud computing, and AI services.54 Additionally, the National Broadband Mission 2.0 aims to extend high-speed broadband connectivity to 270,000 villages by 2030.55 The Indian government’s focus on developing Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) through initiatives like Aadhaar and the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) offers an alternative to China’s digital infrastructure providers, such as Huawei.56 U.S. international development agencies can co-invest with Indian tech firms to enhance digital infrastructure, promote data security, and support the digital economy to build U.S. credibility and weaken the appeal of future Chinese investment while bolstering American public perception on the ground in India.

On the physical side, India requires an estimated $2.2 trillion in infrastructure investment to achieve its goal of becoming a $7 trillion economy by 2030.57 Key areas of interest include transportation modernization, logistics, and urban development. Initiatives like the Prime Minister Gati Shakti National Master Plan aim to provide multi-modal connectivity infrastructure to all economic zones of India.58 U.S. involvement in these projects can facilitate the development of smart cities, enhance key routes and networks for faster trade, and promote sustainable growth through American trust and partnership.

Operational Theatre 2: The Republic of Argentina

Strategic Considerations in Argentina

Along with India, the United States should make Argentina a priority in its efforts to out-compete the BRI, as it fulfills all the necessary conditions of the central strategy. Argentina is located in Latin America—an increasingly relevant battleground region in GPC due to its proximity to the United States.59 Situated in America’s backyard, China “is increasing its economic investments, trade, and grants for big-ticket items like infrastructure projects,” while Russia “exercises influence more through targeted military aid programs, hacking, and propaganda” campaigns.60 These national security threats elevate Latin America as a key region where the United States must protect and defend its strategic interests. Argentina is particularly relevant due to its relative status in the region as one of the wealthiest, most democratic, and militarily capable.61 Furthermore, Argentina’s access to 20% of the world's lithium reserves makes it a supplier of a critical resource necessary for new technology, including rechargeable batteries for electric vehicles – “a sector dominated by China.”62

As for the second prerequisite of stable and inclusive economic institutions, the competitive market economy is a fundamental unit of economic life in Argentina.63 Private companies drive economic production, and the processes for starting and closing a business in Argentina do not involve high barriers to entry.64 Property rights are legally protected. However, it is worth noting that Argentina suffers from high inequality, a “fragmented welfare system,” and occasional “deficiencies and delays” in its judicial system. Argentina’s economy has recently suffered from “high inflation, currency devaluation, and declining real wages” despite some recovery through budget reforms, monetary supply control, and debt management.65 However, it is important to note that the counter-BRI strategy does not necessitate perfect liberal democratic conditions, but sufficient economic rights given to the population that make a country eligible for growth in the future. Argentina meets this. In fact, economists suggest that lasting economic growth in Argentina will come from sustainable increases in investment.66

Argentina’s economy is undergoing rapid transformation. Milei’s austerity measures aim to counter years of irresponsible spending, fostering growth in lithium mining, agritech, and e-commerce.67 Even before Milei, Argentina had significant innovation potential, with major technology companies and unicorn startups emerging in the region. However, Argentina has been strained by the legacy of the Peronist economy and the 1998 economic crisis. The country has faced a bloated state sector, unsustainable pension obligations, a lack of transparency, and unpredictable investor protections among other economic hurdles. However, with the right investments, Argentina could become a major economic partner for the United States, offering opportunities in key industries while helping counterbalance China's influence in the region.

Finally, Argentine President Javier Milei's stance toward China has been, at best, mixed.68 Milei has wavered between criticism, stating that he would not make “pacts with communists,” and pragmatism, meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping to talk international trade.69 This cautious maneuvering of keeping China at an arm’s distance is an opening for the United States to take advantage of. These conditions, in conjunction with one another, create an opportunity for American partnership.

Opportunities in Power Politics

Argentina has historically maintained a strong relationship with China, particularly through its participation in the BRI and a comprehensive strategic partnership.70 Previous Argentine administrations aligned themselves with the Global South, BRICS, and a revisionist economic stance, welcoming greater Chinese partnership.71 Meanwhile, Argentina’s relationship with the U.S. has traditionally been weaker in comparison, though economic and geopolitical factors have kept the two nations engaged. The agricultural sector has been a key point of contention in trade negotiations, with U.S. protectionist policies often limiting deeper economic ties.72

However, under the administration of President Milei, a member of the right-wing La Libertad Avanza coalition, Argentina's foreign policy has shifted. While Argentina remains engaged with China, its ties have slightly weakened, and the Milei administration has expressed interest in strengthening relations with the United States.73 Milei’s strong personal relationship with the Trump administration and his libertarian economic policies suggest Argentina could become a key economic partner for the U.S. in the coming years.74 Argentinian willingness to diversify trade partnerships and reduce reliance on China is most evident through its rotating presidency of Mercosur and recent free trade agreement with the EU.75 With his decline of BRICS’ invitation to join its new international economic order led by the PRC, Russia, Brazil, India, and South Africa, Milei clearly has a distinguishable economic vision from his predecessors.76

One of Argentina’s most significant economic assets is its lithium reserves. Along with Bolivia and Chile, Argentina possesses the world's second-largest lithium deposit, drawing substantial investment from China and Russia.77 The EU is also working to secure a share through the Mercosur trade deal. Meanwhile, the United States has been shifting its lithium supply chains to South America, particularly northern Argentina, but is also investing in domestic production, including a $3 billion project between Lithium Americas Corp. and General Motors in Nevada.78 China, however, is artificially lowering global lithium prices to stifle Western competition.79 Close U.S.-Argentina cooperation in the lithium industry is critical to counteract Chinese economic tactics and secure long-term resource independence.

Chinese and American Investment Trends in Argentina

The United States has a large investment and trade presence in Argentina, specifically in the energy and mining sectors. In 2016, the United States and Argentina entered a Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA), which established the Trade and Investment Council (TIC) as the primary overseer of bilateral trade and investment issues.80 During its last meeting, the TIC and its sister organization, the Innovation and Creativity Forum (ICED Forum), established a Supply Chains Working Group to investigate supply chains in Argentina as alternatives for American companies.81 As of recent reports, the United States stands as the largest foreign investor in Argentina, with $12.6 billion of FDI in 2022.82 Much of this investment is driven by the private sector, not government, meaning that U.S. capital is often tied to corporate priorities and conditions like market efficiency, return on investment, and long-term profitability.83 American companies like Chevron and ExxonMobil have invested heavily in Argentina’s oil and gas fields.84 Furthermore, the Vaca Muerta geologic formation holds the world's second-largest shale gas reserves and fourth-largest for shale oil.85 Argentina’s oil production is seen as “the potential to be a crown jewel for Argentina, which has battled economic crises for years with depleted foreign currency reserves, triple-digit inflation and whipsaw political shifts between left and right.”86 U.S. firms have committed to Argentina’s energy resources in the Vaca Muerta for exploration and early production testing. Investments worth up to $1.24 billion not only enhance Argentina's energy production capabilities but also contribute to job creation and technological advancement within the country.87 Knowingly or not, the private sector has played a significant role in fulfilling the strategic vision of countering the PRC by tying the American and Argentine energy economies together. However, using the international development apparatus, the federal government can facilitate investments that incorporate a strategic calculus.

China has taken an investment approach in Argentina that focuses heavily on renewable energy, lithium extraction, and large-scale infrastructure projects.88 These investments are part of a deliberate strategy by China to secure critical resources and expand its influence across Latin America using the BRI as its vehicle.89 In the renewable energy sector, a flagship example is the Jujuy Province’s Cauchari Solar Plant—a 300 MW photovoltaic power station developed with Chinese financing and technology.90 Completed in 2020, it stands as one of the highest-altitude solar plants in the world, revealing China’s commitment to assist Argentina in diversifying its energy sources and introducing new technologies to local economies.91

China has also injected itself into Argentina’s lithium sector, as it holds some of the world’s largest reserves. Between 2020 and 2023, Chinese companies invested $3.2 billion into seven lithium mining projects, which is nearly double the investment made by U.S. companies.92 American investment has only funded a few projects, such as Salar del Hombre Muerto, in the same time frame.93 Although the lithium forecast has drawn attention from both countries as an industry for strategic investments, as of 2023, China directly received 43% of Argentina’s lithium exports, while the United States accounted for just 11%.94 This speaks to China’s rising dominance of vital lithium supply chains. Since Argentina is located in the lithium triangle, an area with primary access to lithium extraction, it has become an attractive asset for the great powers who understand lithium as essential for producing electric vehicle batteries and energy storage systems. However, lithium experts have warned that China has acquired a skill for making lithium deals and has “a minimum ten-year head start on the United States.”95 The United States has tried to correct for this. In August 2024, the United States and Argentina signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) that commits to “strengthen cooperation in mining investments between the two countries.”96

Outside of lithium, China has also funded rail networks, roads, and hydropower projects through CCP-backed loans and construction partnerships. One major example is the Argentine-Chinese Joint Hydropower Project—which consists of two large dams on the Santa Cruz River and is expected to produce electricity for 1.6 million Argentine families.97 China and Argentina are bound by long-term financial and technical cooperation. While economically attractive deals, the consequence is dependency as China becomes essential to Argentina’s infrastructure, energy independence, and ability to compete globally.

Room for American Investment

From our research, it emerges clearly that Argentina’s lithium deposits are a vast and sought-after resource, attracting the powers seeking dominion over the green technologies of the future. Currently, the PRC retains an influence over the region, which threatens to be amplified by the deregulatory measures of the new government. Argentina’s share of the Lithium Triangle, therefore, is a region deserving attention from the United States, which should expend increased efforts aimed at containing the expansion of the PRC and offering a reliable alternative to Argentina.

To improve America’s influence over the region’s resources, the Trump Administration should invest in Argentine production infrastructure while fostering a high-value-added domestic lithium economy. The tragedy of Chinese lithium-oriented FDI is its extractivist nature. Production plants are built to ship the raw materials to China for processing. This crystallizes an industrial model in which Argentina keeps the fruits only of the lowest-margin phase of the supply chain, creating low value-added and poor regional development, with negative repercussions on the local indigenous communities. American international development investment can help fund and de-risk midstream and downstream activities, helping Argentina retain more value from its natural resources, promote technology transfer, and foster a more integrated domestic industrial base. Offering an alternative to the status quo moves Argentina away from unsustainable extraction-based growth while strengthening bilateral diplomatic and economic ties and improving American lithium supply resilience.

Outside of lithium, Buenos Aires is often referred to as the Silicon Valley of South America. A tech-savvy and highly entrepreneurial population spanning across all social strata leads a growing digital economy, which is gaining international attention. The country was home to 1,200 startups at the end of 2024 – a 25% increase from 2020 – and a considerable number of them have matured.98 Indeed, Argentina is home to twelve unicorns—most notably MercadoLibre and OLX.99 Argentina is a leader within the financial technology industry in Latin America. Its relationships with international funds and national banks have helped financial startups, digital currencies, and blockchain entrepreneurs to thrive. Therefore, local tech talent and international investors have found an excellent opportunity for partnership. U.S. international development agencies can provide targeted financing for fintech startups, fund capacity building, and facilitate more cross-border partnerships and pilots to promote innovation and deepen financial inclusion in Argentina, to the simultaneous benefit of U.S. companies and Argentinians.

Although the country has historically struggled to attract venture capital due mostly to fiscal instability, Argentina, with its developed human capital, is a mature prospect for international markets. Its talent creation is fueled by a highly tech-centered education system, devised in response to a decaying economy in severe need of innovators and entrepreneurs. Argentina’s public universities have ranked 66th globally per the QS University Ranking, leading all South American academic institutions.100 Indeed, it is the “homeland of a vast and well-educated IT community of over 130,000 software developers and engineers,” leading in the region and worldwide.101 Big tech companies (including Google, Oracle, IBM, and Salesforce) hire IT workers and software engineers out of Argentina’s highly qualified tech industry.102 Multinationals look to set up shop in Argentina to capitalize on cheap and high-skilled labor, as “software engineer salaries are 75% lower than in the US.”103 U.S. dollars can establish and scale innovation hubs and match them to U.S. firms in collaborative ventures to deepen U.S.-Argentina integration. Losing talent to China is a heavy cost.

Although the country’s interdependence with China ranges across various sectors, perhaps the most notable is China’s foothold on Argentina’s digital infrastructure. Since 2001, Chinese companies with alleged connections to the PRC – including Huawei and ZTE – “have played a leading role in the country’s telecommunications infrastructure.”104 These Chinese firms also supply Argentina’s telecommunications providers, such as Claro, Movistar, and Personal—many of whom consider Huawei products as an essential part of their business model.105 In September 2023, then Minister of the Economy Sergio Massa put the country’s 5G bandwidth for auction to raise funds to help restore the country’s unsustainable deficit.106 Although the fate of the auction is still unclear due to the government’s inability to conduct the bid in time, companies operating in Huawei servers were “poised to win” the deal.107

Domination over the telecom infrastructure network is a strategic asset for the PRC. This type of network is one of the most lethal instruments of weaponized interdependence, where China seeks to extract victories from Argentina while locking Argentina into asymmetric dependence. As Milei has expressed an interest in diversifying, the provision of telecom infrastructure could be a very fruitful and strategic pursuit for American companies to bring forward.

Tactical Level Institutional Design Changes

To optimize American investment in these operational theatres, the United States must employ its strong and robust international development institutions. The administration has signaled that the State Department, DFC, and MCC in their current states are unable to meet the demands of strategic competition.

It is worth acknowledging that these 3 agencies have been or are expected to be severely cut by the current administration. The new strategy of how to wield them more effectively is the precise reason as to why these institutions are worth preserving. As such, this paper makes the case that these international development agencies must not only be sustained as a core element of American soft power but kept to serve strategic functions. Following the Administration’s federal workforce reorganization, their authorities should be consolidated and include dual-purpose strategic aims. This approach gives competitive objectives more weight in the international development decision-making process. We advise the administration to consider the following recommendations to better employ the tactical vehicles of American investment, namely, our international development agencies:

Create an overarching Strategic Development Policy Directive that aligns USAID, DFC, and MCC under a unified set of geopolitical and development goals. Alternatively, we recommend the creation of a Development and Strategic Engagement Directorate within the NSC to coordinate development policy as a tool of national security. To compete effectively in key operational theatres, the United States must unify the efforts of its international development institutions under a common mandate so that they operate in synergy, guided by shared priorities.

Require agencies to evaluate projects on both developmental impact and strategic alignment. To adapt to the realities of GPC, U.S. international development agencies must modernize their decision-making frameworks to assess proposals not only for their potential to serve development objectives but also for their alignment with broader U.S. geopolitical interests. Agencies should adopt a dual-metric evaluation model that measures development impact alongside strategic value—such as countering malign influence, reinforcing regional stability, or securing critical supply chains. While some development professionals will likely object to instrumentalizing U.S. assistance in this way, it is important to note that strategic priorities do not necessarily supersede development and humanitarian missions. The goal here is to more deeply embed strategic thinking into the calculus of project funding abroad.

Expand agency mandates to include strategic infrastructure investments and supply chain security. Current statutory limitations constrain the ability of USAID, DFC, and MCC to proactively support projects that, while not purely developmental, are critical to U.S. strategic interests.108 Agencies should be authorized and resourced to invest in strategic infrastructure – from digital connectivity and energy resilience to transportation corridors and port modernization – that bolsters bilateral relations and reduces partner nations’ reliance on adversarial powers. Additionally, mandates should explicitly include strengthening supply chain resilience in key sectors like semiconductors, critical minerals, and medical goods. These strategic investments not only serve host nations but also reinforce U.S. power abroad.

A New Way of Thinking

The Trump Administration must do two seemingly contradictory things: prioritize America First and compete with China using its partners. However, this paper reveals that they are not contradictory, at least in the context of the BRI. Using the framework outlined above, we believe the United States can approach investment from our international development agencies in a more calculated process to counter China's expanding capture of countries across the Global South. At its core, this framework is a novel way of thinking. The real contribution of this paper is the methodology behind how and when to employ economic statecraft more effectively in high-value target countries. Whether the United States likes it or not, GPC is here to stay, and maintaining a competitive edge requires the pursuit of favorable economic relations. The alternative choice? Decline from hegemony.

Melisa Altintas, Ashton Basak, Zubin Battaglia, Maya Belorusskiy, Kristina Georgieva, Rohan Jois, and Luke Madden are undergraduate students at Georgetown University's School of Foreign Service. They are economic statecraft researchers for The Concord Group, a national security policy talent accelerator built to meet the challenge of 21st-century strategic competition.

James McBride, Noah Berman, and Andrew Chatzky, “China’s Massive Belt and Road Initiative,” Council on Foreign Relations, February 2, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-massive-belt-and-road-initiative.↩︎

McBride, Berman, and Chatzky, “China’s Massive Belt and Road Initiative.”↩︎

Andreea Brinza, “Biden’s ‘Build Back Better World’ Is an Empty Competitor to China,” Foreign Policy, June 29, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/06/29/biden-build-back-better-world-belt-road-initiative/.↩︎

“China’s Foreign Investments Significantly Outpace the United States. What Does That Mean?,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, October 16, 2024, https://www.gao.gov/blog/chinas-foreign-investments-significantly-outpace-united-states.-what-does-mean.↩︎

“China’s Foreign Investments Significantly Outpace the United States. What Does That Mean?”↩︎

Andrew S. Harvey, “The Levels of War as Levels of Analysis,” Army University Press, November 2021, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/November-December-2021/Harvey-Levels-of-War/.↩︎

“Foreign Assistance Dashboard,” n.d., https://foreignassistance.gov/.↩︎

“Foreign Assistance Dashboard.”↩︎

“Introduction to Geopolitics,” CFA Institute, n.d., https://www.cfainstitute.org/insights/professional-learning/refresher-readings/2024/introduction-geopolitics.↩︎

Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (Crown Currency, 2013).↩︎

Stephen M. Walt, “Why Is America so Bad at Promoting Democracy in Other Countries?,” Foreign Policy, April 25, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/04/25/why-is-america-so-bad-at-promoting-democracy-in-other-countries/.↩︎

Warsaw Institute, “China and the ‘Malacca Dilemma,’” February 28, 2021, https://warsawinstitute.org/china-malacca-dilemma/.↩︎

Sabine Donner, Hauke Hartmann, and Sabine Steinkamp, “BTI Transformation Index: India Country Report 2024,” Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2024, https://bti-project.org/en/reports/country-report/IND.↩︎

“Freedom in the World 2024: India,” Freedom House, 2024, https://freedomhouse.org/country/india/freedom-world/2024.↩︎

Shaikh Azizur Rahman, “India Protests Chinese Map Claiming Disputed Territories,” Voice of America, August 30, 2023, https://www.voanews.com/a/india-protests-chinese-map-claiming-disputed-territories/7246891.html.↩︎

Murali Krishnan, “India’s Modi to Boost Trade, Defense Ties in US Visit,” Deutsche Welle, February 11, 2025, https://www.dw.com/en/indias-modi-to-boost-trade-defense-ties-in-us-visit/a-71571323.↩︎

Soutik Biswas and Nikhil Inamdar, “Modi-Trump Talks: Five Key Takeaways,” BBC, February 14, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c23ndleveymo.↩︎

Nandita Bose, Trevor Hunnicutt, and David Brunnstrom, “India, US Agree to Resolve Trade and Tariff Rows After Trump-Modi Talks,” Reuters, February 14, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/indias-modi-brings-tariff-gift-trump-talks-2025-02-13/.↩︎

Bose, Hunnicutt, and Brunnstrom, “India, US Agree to Resolve Trade and Tariff Rows After Trump-Modi Talks.”↩︎

TOI Business Desk, “US Overtakes UAE to Become India’s 4th Largest Crude Oil Supplier; Russia Still Tops the Chart,” The Times of India, May 16, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/us-overtakes-uae-to-become-indias-4th-largest-crude-oil-supplier-russia-still-tops-the-chart/articleshow/121204301.cms.↩︎

“India Has Bought American Weapons Worth $20 Billion Since 2008,” Amritt, February 14, 2025, https://amritt.com/the-india-expert-blog/india-has-bought-american-weapons-worth-20-billion-since-2008/.↩︎

Nidhi Verma, “India’s BPCL Says Russia Oil Intake Share Falls to 34% in September Quarter,” Reuters, October 28, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/indias-bpcl-says-russia-oil-intake-share-falls-34-september-quarter-2024-10-28/.↩︎

The White House, “United States-India Joint Leaders’ Statement,” February 13, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/02/united-states-india-joint-leaders-statement/.↩︎

“Key Takeaways From Donald Trump’s Meeting With India’s Narendra Modi,” Al Jazeera, February 14, 2025, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/2/14/key-takeaways-from-donald-trumps-meeting-with-indias-narendra-modi.↩︎

“China Global Investment Tracker,” American Enterprise Institute, n.d., https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/.↩︎

“China Global Investment Tracker.”↩︎

“China Global Investment Tracker.”↩︎

“China Global Investment Tracker.”↩︎

“China Global Investment Tracker.”↩︎

Qian Zhou and Giulia Interesse, “China-India Economic Ties: Trade, Investment, and Opportunities,” China Briefing News, October 11, 2024, https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-india-economic-ties-trade-investment-and-opportunities/.↩︎

Zhou and Interesse, “China-India Economic Ties: Trade, Investment, and Opportunities.”↩︎

Vijaya Subrahmanyam, Penelope Prime, and Usha Nair Reichert, “India’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment in the Context of China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” China Currents 23, no. 1 (2024), https://www.chinacenter.net/2024/china-currents/23-1/indias-outward-foreign-direct-investment-in-the-context-of-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative/.↩︎

Tanveer Ahmad Khan, “Limited Hard Balancing: Explaining India’s Counter Response to Chinese,” Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs 6, no. 3 (April 2023), 97 https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/Display/Article/3371481/limited-hard-balancing-explaining-indias-counter-response-to-chinese-encircleme/.↩︎

“US Continues to Be Largest Source of FDI in India: RBI Census,” The Economic Times, October 11, 2024, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/finance/us-continues-to-be-largest-source-of-fdi-in-india-rbi-census/articleshow/114153704.cms?from=mdr.↩︎

“Foreign Assistance Dashboard.”↩︎

Richard M. Rossow, “India’s Ascending Role for U.S. Economic Security,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 29, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/indias-ascending-role-us-economic-security.↩︎

Joshua Sullivan and Jon Bateman, “China Decoupling Beyond the United States: Comparing Germany, Japan, and India,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 8, 2025, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2025/01/china-decoupling-beyond-the-united-states-comparing-germany-japan-and-india?lang=en.↩︎

Sullivan and Bateman, “China Decoupling Beyond the United States: Comparing Germany, Japan, and India.”↩︎

Subrahmanyam, Prime, and Reichert, “India’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment in the Context of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.”↩︎

Matt Ingeneri, “2022 Investment Climate Statements: India,” U.S. Department of State, 2022, https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-investment-climate-statements/india/.↩︎

James Fox, “FDI Policy in India: Impact on Investments From China-Linked Entities,” India Briefing, August 18, 2022, https://www.india-briefing.com/news/india-fdi-policy-china-companies-associated-entities-security-concerns-approvals-25534.html/.↩︎

Rahman, “India Protests Chinese Map Claiming Disputed Territories.”↩︎

“China Global Investment Tracker.”↩︎

“China Global Investment Tracker.”↩︎

H. S. Sudhira, “Biopharma Industry in India: Vaccines,” BioSpectrum, August 30, 2024, https://www.biospectrumindia.com/features/95/25188/biopharma-industry-in-india-vaccines.html.↩︎

“Indian Pharmaceutical Industry,” India Brand Equity Foundation, February 2025, https://www.ibef.org/industry/pharmaceutical-india.↩︎

Priyali Sur, “The Coronavirus Exposed the US’ Reliance on India for Generic Drugs. But That Supply Chain Is Ultimately Controlled by China,” CNN, May 16, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/16/business-india/india-pharma-us-china-supply-china-intl-hnk.↩︎

“Why India Could Become the Next Big Investment Opportunity for the US,” HSBC, December 5, 2024, https://www.business.hsbc.com/en-gb/insights/international/india-next-big-investment-opportunity-for-us.↩︎

Jacob Koshy, “Plan to Install 500 GW of Renewable Energy Capacity by 2030 to Cost ₹2.44 Trillion,” The Hindu, December 9, 2022, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/cost-of-transmitting-clean-energy-in-india-to-exceed-2-trillion/article66235468.ece.↩︎

“India Must Double Renewable Capacity Additions to Meet 2030 Clean-energy Targets, Report Says,” Reuters, February 25, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/india-must-double-renewable-capacity-additions-meet-2030-clean-energy-targets-2025-02-26/.↩︎

“Generating Energy Capacity in India by Countering China’s Manufacturing Dominance,” U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, 2023, https://www.dfc.gov/investment-story/generating-energy-capacity-india-countering-chinas-manufacturing-dominance.↩︎

“Generating Energy Capacity in India by Countering China’s Manufacturing Dominance.”↩︎

“Generating Energy Capacity in India by Countering China’s Manufacturing Dominance.”↩︎

Kailash Babar, “India Data Center Capacity to Double in 3 Years, Capex Requirement Rs 50,000 Crore,” The Economic Times, March 27, 2024, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/services/property-/-cstruction/india-data-center-capacity-to-double-in-3-years-capex-requirement-rs-50000-crore/articleshow/108811453.cms?from=mdr.↩︎

“NATIONAL BROADBAND MISSION 2.0,” Department of Telecommunications, Government of India, 2025, https://eservices.dot.gov.in/sites/default/files/user-mannual/NBM%202-0%20Vision%20Document_Final_RoW-compressed.pdf.↩︎

Satwik Mishra and Amitabh Kant, “The International Significance of India’s Digital Public Infrastructure,” World Economic Forum, August 23, 2023, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/08/the-international-significance-of-indias-digital-public-infrastructure/.↩︎

“India Needs $2.2 Trillion Investment on Infra to Become 7$ Trillion Economy by 2030: Report,” The Economic Times, December 12, 2024, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/infrastructure/india-needs-2-2-trillion-investment-on-infra-to-become-7-trillion-economy-by-2030-report/articleshow/116243849.cms?from=mdr.↩︎

“PM Gati Shakti - National Master Plan for Multi-modal Connectivity,” National Portal of India, n.d., https://www.india.gov.in/spotlight/pm-gati-shakti-national-master-plan-multi-modal-connectivity.↩︎

Ryan C. Berg, “The Importance of Democracy Promotion to Great Power Competition in Latin America and the Caribbean,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, September 26, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/importance-democracy-promotion-great-power-competition-latin-america-and-caribbean.↩︎

Adam Isacson, “Great-Power Competition Comes for Latin America,” War on the Rocks, February 24, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/02/great-power-competition-comes-for-latin-america/.↩︎

Frank Okata, “To Counter China in Latin America, Focus on Argentina,” Proceedings - U.S. Naval Institute 148 (August 2022), https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2022/august/counter-china-latin-america-focus-argentina.↩︎

Samir Tata, “Argentina Presents a Huge Geostrategic Opportunity for the US,” The Hill, May 13, 2025, https://thehill.com/opinion/international/5296652-argentina-presents-a-huge-geostrategic-opportunity-for-the-us/.↩︎

Sabine Donner, Hauke Hartmann, and Sabine Steinkamp, “BTI Transformation Index: Argentina Country Report 2024,” Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2024, https://bti-project.org/en/reports/country-report/ARG.↩︎

Donner, Hauke Hartmann, and Steinkamp, “BTI Transformation Index: Argentina Country Report 2024.”↩︎

Daniel Zaga, Federico Di Yenno, and Juan Ignacio Lacapmesure, “Argentina Economic Outlook, November 2024,” Deloitte, November 8, 2024, https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/economy/americas/argentina-economic-outlook.html.↩︎

Alejo Czerwonko, “Can Radical Reform Unlock Argentina’s Long-awaited Economic Recovery?,” World Economic Forum, May 20, 2025, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/05/argentina-radical-reform-unlock-economic-recovery/.↩︎

Ian Vásquez, “Deregulation in Argentina: Milei Takes ‘Deep Chainsaw’ to Bureaucracy and Red Tape,” Free Society - CATO Institute 2, no. 1 (2025), 27, https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/2025-03/FS_Volume02-Issue-01.pdf.↩︎

Juan Manuel Harán, “From Tension to Understanding: Argentina-China Relations Under Milei,” The Diplomat, November 16, 2024, https://thediplomat.com/2024/11/from-tension-to-understanding-argentina-china-relations-under-milei/.↩︎

Jaime Rosemberg, “‘No Hago Pactos Con Comunistas’: Milei Quiere Romper Relaciones Con China Y Brasil En Caso De Llegar a La Presidencia,” LA NACION, August 17, 2023, https://www.lanacion.com.ar/politica/no-hago-pactos-con-comunistas-milei-quiere-romper-relaciones-con-china-y-brasil-en-caso-de-llegar-a-nid17082023/.↩︎

Evan Ellis, “The Evolution of Chinese Engagement in Argentina Under Javier Milei,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 5, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/evolution-chinese-engagement-argentina-under-javier-milei.↩︎

Ellis, “The Evolution of Chinese Engagement in Argentina Under Javier Milei.”↩︎

“US Official Admits No More Meat to Be Bought From Argentina,” MercoPress, April 11, 2025, https://en.mercopress.com/2025/04/11/us-official-admits-no-more-meat-to-be-bought-from-argentina.↩︎

Ariel González Levaggi and Claudio Robelo, “Argentina’s Realignment With the United States: Milei’s Reforms Gain Strategic Support,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, April 30, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/argentinas-realignment-united-states-mileis-reforms-gain-strategic-support.↩︎

Levaggi and Robelo, “Argentina’s Realignment With the United States: Milei’s Reforms Gain Strategic Support.”↩︎

Federico Steinberg, “What Are the Implications of the EU–Mercosur Free Trade Agreement?,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 6, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/what-are-implications-eu-mercosur-free-trade-agreement.↩︎

Robert Plummer, “Argentina Pulls Out of Plans to Join Brics Bloc,” BBC, December 29, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-67842992.↩︎

Ryan C. Berg and T. Andrew Sady-Kennedy, “South America’s Lithium Triangle: Opportunities for the Biden Administration,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, August 17, 2021, https://www.csis.org/analysis/south-americas-lithium-triangle-opportunities-biden-administration.↩︎

Lithium Americas Corp., “Unlocking Thacker Pass: General Motors to Contribute Combined $625 Million in Cash and Letters of Credit to New Joint Venture With Lithium Americas,” Press release, October 16, 2024, https://lithiumamericas.com/news/news-details/2024/Unlocking-Thacker-Pass-General-Motors-to-Contribute-Combined-625-Million-in-Cash-and-Letters-of-Credit-to-New-Joint-Venture-with-Lithium-Americas/default.aspx.↩︎

Sergio Gonclaves, “China Is Oversupplying Lithium to Eliminate Rivals, US Official Says,” Reuters, October 8, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/china-is-oversupplying-lithium-eliminate-rivals-us-official-says-2024-10-08/.↩︎

“Argentina,” United States Trade Representative, n.d., https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/americas/argentina.↩︎

“Argentina.”↩︎

U.S. Mission Argentina, “U.S. RELATIONS WITH ARGENTINA,” U.S. Embassy in Argentina, February 23, 2024, https://ar.usembassy.gov/u-s-relations-with-argentina-fact-sheet/.↩︎

“2024 Investment Climate Statements: Argentina,” U.S. Department of State, 2024, https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-investment-climate-statements/argentina/.↩︎

“Argentina Country Commercial Guide: Energy - Oil & Gas,” International Trade Administration, November 2, 2023, https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/argentina-energy-oil-gas.↩︎

Alexander Villegas and Eliana Raszewski, “In Argentina’s Vaca Muerta Shale Lands, It’s Drill, Baby, Drill!,” Reuters, October 23, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/argentinas-vaca-muerta-shale-lands-its-drill-baby-drill-2024-10-23/.↩︎

Villegas and Raszewski, “In Argentina’s Vaca Muerta Shale Lands, It’s Drill, Baby, Drill!”↩︎

Alejandro Lifschitz and Karina Grazina, “Chevron, Argentina’s YPF Sign $1.24 Billion Vaca Muerta Shale Deal,” Reuters, July 16, 2013, https://www.reuters.com/article/business/chevron-argentinas-ypf-sign-124-billion-vaca-muerta-shale-deal-idUSBRE96F18Y/.↩︎

“China Global Investment Tracker.”↩︎

Tatiana Gélvez Rubio and Juliana González Jáuregui, “Chinese Overseas Finance in Renewable Energy in Argentina and Brazil: Implications for the Energy Transition,” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 51, no. 1 (July 7, 2022), 138, https://doi.org/10.1177/18681026221094852.↩︎

Cassandra Garrison, “On South America’s Largest Solar Farm, Chinese Power Radiates,” Reuters, April 23, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/business/environment/on-south-americas-largest-solar-farm-chinese-power-radiates-idUSKCN1RZ0B1/.↩︎

“Cauchari Solar Project, Jujuy,” NS Energy, November 19, 2019, https://www.nsenergybusiness.com/projects/cauchari-solar-project-jujuy/.↩︎

Gustavo Cardozo, “The Lithium Battle: Strategies of China and U.S. in Argentina,” Institute for Security and Development Policy, August 21, 2024, https://www.isdp.eu/the-lithium-battle-strategies-of-china-and-u-s-in-argentina/.↩︎

“Hombre Muerto North Lithium Project,” Lithium South Development Corporation, n.d., https://www.lithiumsouth.com/projects/.↩︎

Cardozo, “The Lithium Battle: Strategies of China and U.S. in Argentina.”↩︎

David Feliba, “Lithium Tug of War: The US-China Rivalry for Argentina’s White Gold,” Climate Home News, June 17, 2024, https://www.climatechangenews.com/2024/06/17/lithium-tug-of-war-the-us-china-rivalry-for-argentinas-white-gold/.↩︎

Facundo Iglesia, “US And Argentina Sign Agreement to Strengthen Mining Investments,” Buenos Aires Herald, August 23, 2024, https://buenosairesherald.com/world/international-relations/us-and-argentina-sign-agreement-to-strengthen-mining-investments.↩︎

“Argentine President Calls Argentina-China Hydropower Project ‘Highly Important,’” Xinhua News Agency, January 16, 2019, https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/p/77500.html.↩︎

Ludo Fourrage, “Inside Argentina’s Thriving Tech Hub: Startups and Success Stories,” Nucamp, December 23, 2024, https://www.nucamp.co/blog/coding-bootcamp-argentina-arg-inside-argentinas-thriving-tech-hub-startups-and-success-stories.↩︎

“GTIPA Perspectives: The Importance of E-commerce, Digital Trade, and Maintaining the WTO E-commerce Customs Duty Moratorium,” Global Trade and Innovation Policy Alliance, October 2020, 9, https://www2.itif.org/2020-gtipa-e-commerce.pdf.↩︎

Lisa Dahlgren, “Hire Tech Talent in Argentina,” Teilur Talent, August 12, 2024, https://www.teilurtalent.com/insights/hire-tech-talent-in-argentina.↩︎

Dahlgren, “Hire Tech Talent in Argentina.”↩︎

Dahlgren, “Hire Tech Talent in Argentina.”↩︎

Dahlgren, “Hire Tech Talent in Argentina.”↩︎

Ellis, “The Evolution of Chinese Engagement in Argentina Under Javier Milei.”↩︎

Ellis, “The Evolution of Chinese Engagement in Argentina Under Javier Milei.”↩︎

Ellis, “The Evolution of Chinese Engagement in Argentina Under Javier Milei.”↩︎

Ellis, “The Evolution of Chinese Engagement in Argentina Under Javier Milei.”↩︎

William Henagan, “Reauthorizing DFC: A Primer for Policymakers,” Council on Foreign Relations, March 31, 2025, https://www.cfr.org/article/reauthorizing-dfc-primer-policymakers.↩︎